Beginnings and ends of years are only a convention, of course. The Gregorian New Year we're about to observe is particularly weird, it seems to me, though I suppose you could make a case that the roaming Chinese lunar new year (January 26 in 2009, February 14 -- hey, that'll be Valentine's day! -- in 2010) is more so.

In any case, it's true that you might as well take stock of your life, or your year, at any point in the year, but January 1 is good enough for me, not least because it's also my birthday, another one of those stock-taking days.

Jon Swift is no longer blogging, and one of the lesser losses as a result of his retirement is that he's no longer inviting other bloggers to nominate their own best posts of the year. Like Avedon at The Sideshow, then, I'll blow my own horn here. My favorite post of 2009, the one I most wish everyone would read, is "Dude, I'm a Fag," my discussion of the cost of gay respectability and assimilation. ("Assimilation" is a dodgy word when applied to gay people, I know, and if I made New Year's resolutions, one would be to follow up on that statement soon.) It got more attention in terms of links and readers than any other single piece I've written for this blog, and I'm proud of it. (Along with its followup.)

I sometimes feel -- not guilty, exactly, but I'm not sure what the right word would be -- I feel strange that I live in a city where unemployment is much lower than the national rate, and that I have a stable job with benefits, when so many people don't. During the break, when I've been out and about a lot, I've become aware of how many of the people who hang out around the public library and the bus station are homeless. Yesterday afternoon, for example, I saw a man with the telltale overstuffed backpack and heavy clothing asking a couple, "Do you have a place to stay tonight?" The temperature dropped from a not-too-bad 37 to this morning's 10 degrees F. Another resolution-if-I-made-one is going to be to start making some regular donations to the local food bank and free kitchens.

Anyone who's read this blog will know that I haven't been disappointed by President Obama's performance: my predictions from before he took office have been borne out abundantly. The only thing that disappoints me, just a little, is my own inability to do the "I Told You So" dance at his supporters. But on the whole, I suppose that shows me to be a better person than the Obama fans, who've behaved just as badly since he took office as they did before. It's significant, I think, that this blogger at The Nation, listing "some under-appreciated progressive victories that should inspire hope for 2010", doesn't mention Obama once. Which is the best attitude to take, I think -- as I've pointed out before, the real victories aren't the occasional crumbs the rulers throw us, it's the ones we take for ourselves. Time to abandon Big Man worship in favor of mass action. If I can just find the right mass to join...

And that reminds me, I finally found one of the articles I've been looking for about the effectiveness of Democratic abusiveness to voters on their left. This is an interesting interview from Counterpunch in 2003. Obviously, Sam Smith's question was never answered, and unfortunately, given Obama's victory in 2008, it's unlikely that the lesson was ever learned:

What I tell my Democratic friends is that if they want my vote they have to treat me at least as nice as a soccer mom or one of their corporate campaign contributors. How come, I ask, Greens are the only constituency in history that you think you can convince by hectoring them? What are you going to do for my vote? I ask. And they look at me perplexed.

Another good line from the same interview: "Polls are the standardized test used by the media to determine how well we have learned what it has taught us."

What a Long, Strange Year It's Been

Beginnings and ends of years are only a convention, of course. The Gregorian New Year we're about to observe is particularly weird, it seems to me, though I suppose you could make a case that the roaming Chinese lunar new year (January 26 in 2009, February 14 -- hey, that'll be Valentine's day! -- in 2010) is more so.

In any case, it's true that you might as well take stock of your life, or your year, at any point in the year, but January 1 is good enough for me, not least because it's also my birthday, another one of those stock-taking days.

Jon Swift is no longer blogging, and one of the lesser losses as a result of his retirement is that he's no longer inviting other bloggers to nominate their own best posts of the year. Like Avedon at The Sideshow, then, I'll blow my own horn here. My favorite post of 2009, the one I most wish everyone would read, is "Dude, I'm a Fag," my discussion of the cost of gay respectability and assimilation. ("Assimilation" is a dodgy word when applied to gay people, I know, and if I made New Year's resolutions, one would be to follow up on that statement soon.) It got more attention in terms of links and readers than any other single piece I've written for this blog, and I'm proud of it. (Along with its followup.)

I sometimes feel -- not guilty, exactly, but I'm not sure what the right word would be -- I feel strange that I live in a city where unemployment is much lower than the national rate, and that I have a stable job with benefits, when so many people don't. During the break, when I've been out and about a lot, I've become aware of how many of the people who hang out around the public library and the bus station are homeless. Yesterday afternoon, for example, I saw a man with the telltale overstuffed backpack and heavy clothing asking a couple, "Do you have a place to stay tonight?" The temperature dropped from a not-too-bad 37 to this morning's 10 degrees F. Another resolution-if-I-made-one is going to be to start making some regular donations to the local food bank and free kitchens.

Anyone who's read this blog will know that I haven't been disappointed by President Obama's performance: my predictions from before he took office have been borne out abundantly. The only thing that disappoints me, just a little, is my own inability to do the "I Told You So" dance at his supporters. But on the whole, I suppose that shows me to be a better person than the Obama fans, who've behaved just as badly since he took office as they did before. It's significant, I think, that this blogger at The Nation, listing "some under-appreciated progressive victories that should inspire hope for 2010", doesn't mention Obama once. Which is the best attitude to take, I think -- as I've pointed out before, the real victories aren't the occasional crumbs the rulers throw us, it's the ones we take for ourselves. Time to abandon Big Man worship in favor of mass action. If I can just find the right mass to join...

And that reminds me, I finally found one of the articles I've been looking for about the effectiveness of Democratic abusiveness to voters on their left. This is an interesting interview from Counterpunch in 2003. Obviously, Sam Smith's question was never answered, and unfortunately, given Obama's victory in 2008, it's unlikely that the lesson was ever learned:

What I tell my Democratic friends is that if they want my vote they have to treat me at least as nice as a soccer mom or one of their corporate campaign contributors. How come, I ask, Greens are the only constituency in history that you think you can convince by hectoring them? What are you going to do for my vote? I ask. And they look at me perplexed.

Another good line from the same interview: "Polls are the standardized test used by the media to determine how well we have learned what it has taught us."

In any case, it's true that you might as well take stock of your life, or your year, at any point in the year, but January 1 is good enough for me, not least because it's also my birthday, another one of those stock-taking days.

Jon Swift is no longer blogging, and one of the lesser losses as a result of his retirement is that he's no longer inviting other bloggers to nominate their own best posts of the year. Like Avedon at The Sideshow, then, I'll blow my own horn here. My favorite post of 2009, the one I most wish everyone would read, is "Dude, I'm a Fag," my discussion of the cost of gay respectability and assimilation. ("Assimilation" is a dodgy word when applied to gay people, I know, and if I made New Year's resolutions, one would be to follow up on that statement soon.) It got more attention in terms of links and readers than any other single piece I've written for this blog, and I'm proud of it. (Along with its followup.)

I sometimes feel -- not guilty, exactly, but I'm not sure what the right word would be -- I feel strange that I live in a city where unemployment is much lower than the national rate, and that I have a stable job with benefits, when so many people don't. During the break, when I've been out and about a lot, I've become aware of how many of the people who hang out around the public library and the bus station are homeless. Yesterday afternoon, for example, I saw a man with the telltale overstuffed backpack and heavy clothing asking a couple, "Do you have a place to stay tonight?" The temperature dropped from a not-too-bad 37 to this morning's 10 degrees F. Another resolution-if-I-made-one is going to be to start making some regular donations to the local food bank and free kitchens.

Anyone who's read this blog will know that I haven't been disappointed by President Obama's performance: my predictions from before he took office have been borne out abundantly. The only thing that disappoints me, just a little, is my own inability to do the "I Told You So" dance at his supporters. But on the whole, I suppose that shows me to be a better person than the Obama fans, who've behaved just as badly since he took office as they did before. It's significant, I think, that this blogger at The Nation, listing "some under-appreciated progressive victories that should inspire hope for 2010", doesn't mention Obama once. Which is the best attitude to take, I think -- as I've pointed out before, the real victories aren't the occasional crumbs the rulers throw us, it's the ones we take for ourselves. Time to abandon Big Man worship in favor of mass action. If I can just find the right mass to join...

And that reminds me, I finally found one of the articles I've been looking for about the effectiveness of Democratic abusiveness to voters on their left. This is an interesting interview from Counterpunch in 2003. Obviously, Sam Smith's question was never answered, and unfortunately, given Obama's victory in 2008, it's unlikely that the lesson was ever learned:

What I tell my Democratic friends is that if they want my vote they have to treat me at least as nice as a soccer mom or one of their corporate campaign contributors. How come, I ask, Greens are the only constituency in history that you think you can convince by hectoring them? What are you going to do for my vote? I ask. And they look at me perplexed.

Another good line from the same interview: "Polls are the standardized test used by the media to determine how well we have learned what it has taught us."

Labels:

new year

Gold to Commodities - Back the Other Way

src="http://pagead2.googlesyndication.com/pagead/show_ads.js">

src="http://pagead2.googlesyndication.com/pagead/show_ads.js">

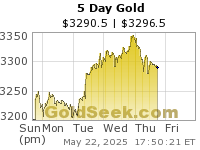

The ratio of the nominal Gold price to the nominal price of a basket of commodities (i.e. the "real" price of Gold as Bob Hoye calls it) is now oversold enough to cause a swing back the other way for several weeks. This should correspond with a nice swing higher in the Gold stock sector.

Here's a 1 year chart of the Gold price ($GOLD) divided by the $CCI commodities index (i.e. a $GOLD:$CCI ratio chart):

Again, I don't use this ratio as a trading signal, rather as a fundamental underpinning. I think in this case the fundamentals and Gold stock price indices will rise at the same time, as both are oversold and the $GOLD:$CCI ratio is already at multi-decade highs, so a small bump in this ratio should be all that's needed to vault the Gold sector higher as 2010 begins. I, for one, continue to believe it is going to be a MAJOR move higher in Gold stocks.

Happy New Year!

My Brother's Keeper II

It's now a year since the beginning of Operation Cast Lead, the Israeli blitzkrieg of Gaza. Uri Avnery has a good retrospective on it at Counterpunch, showing that it was at best an ambiguous victory for Israel. The siege of Gaza goes on, however, with the US Army Corps of Engineers working with Israel to maintain it. A large protest, the Gaza Freedom March, is simmering in Cairo, to the great discomfort of the Egyptian government; the participation of Hedy Epstein, an 85-year-old Holocaust survivor from St. Louis, adds to the bad PR for both Israel and Egypt.

It's now a year since the beginning of Operation Cast Lead, the Israeli blitzkrieg of Gaza. Uri Avnery has a good retrospective on it at Counterpunch, showing that it was at best an ambiguous victory for Israel. The siege of Gaza goes on, however, with the US Army Corps of Engineers working with Israel to maintain it. A large protest, the Gaza Freedom March, is simmering in Cairo, to the great discomfort of the Egyptian government; the participation of Hedy Epstein, an 85-year-old Holocaust survivor from St. Louis, adds to the bad PR for both Israel and Egypt.But I want to write about a startling post on the Israel-Palestine conflict by Stephen Vizinczey on his blog. It's hard to believe this was actually written by Vizinczey, who wrote some insightful analysis of Soviet and American imperialism in the past. But, it seems, like many people his insight breaks down where Israel is concerned. He wrote:

The recent condemnation of Israel is a fine example of the selective outrage that ensures that there will never be peace on Earth. “We rain rockets on the Israelis, on their farms, on their nurseries, their schools. We explode bombs in their restaurants, in their supermarkets – we are going to wipe Israel off the face of the Earth! But they are so evil, they want to live, they get angry, they hit back, they try to defend themselves! Condemn them!”This makes no sense on any level. To begin at the surface, who is supposed to be speaking in his imagined quotation? Since it purports to be a "we" who "rain rockets on the Israelis," it would have to be Hamas, or since Hamas stopped firing rockets into Israel, various small independent Palestinian factions. (The bit about wiping Israel off the face of the Earth is a giveaway too.) According to Avnery, though, "The Qassams have stopped almost completely. Hamas has even imposed its authority on the small, extreme factions, which wanted to continue." Of course such groups would condemn Israel, and there's nothing "selective" about it. (Does Vizinczey expect the Palestinians to "rain rockets" on North Korea? The US?)

But Vizinczey isn't just angry at the Gazans; it seems that he's blaming everyone in the world who condemned Operation Cast Lead, none of whom rained rockets on the Israelis. Perhaps he means that Archbishop Tutu, Israeli combat veterans, Jimmy Carter (though he has recently recanted, or at least backtracked), and Roger Waters of Pink Floyd all figuratively rained rockets on Israel, or figuratively cheered on the rockets. It would have to be figuratively, or literally in the sense of figuratively, because virtually all the critics of the attack on Gaza were scrupulous in condemning rocket attacks on Israel.

As Vizinczey must know, the reason for the widespread condemnation of Operation Cast Lead, as of the 2006 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, was not that the Israelis were defending themselves, but that they were going so far beyond defense. Israeli casualties during Operation Cast Lead were one percent of Palestinian casualties; a similar disproportion has characterized most Israeli violence against the Palestinians. Indeed, many of the charges made against Hizbollah in Lebanon and against Hamas in Gaza turn out to be true of Israel instead: breaking ceasefires, for example, or using civilians as human shields.

The Stephen Vizinczey who dissected American justifications of its massive violence in Vietnam would have recognized this. The Stephen Vizinczey who jeered at white attempts to demonize slave resistance would have recognized this. The Stephen Vizinczey who fought in the 1956 Hungarian uprising against the Soviet Union would have recognized this. But today's Stephen Vizinczey joins the Israelis raining missiles on Lebanon; no doubt he would have joined the schoolgirls who signed their names on missiles waiting to be fired. This Stephen Vizinczey joins the Hasidim placidly watching the smoke rising above Gaza from a nearby hilltop. The Palestinians are so evil, they want to live, they get angry, they hit back, they try to defend themselves! Condemn them! Yes, there is selective outrage here, but it isn't the critics of Israel who are guilty of it.

The Stephen Vizinczey who dissected American justifications of its massive violence in Vietnam would have recognized this. The Stephen Vizinczey who jeered at white attempts to demonize slave resistance would have recognized this. The Stephen Vizinczey who fought in the 1956 Hungarian uprising against the Soviet Union would have recognized this. But today's Stephen Vizinczey joins the Israelis raining missiles on Lebanon; no doubt he would have joined the schoolgirls who signed their names on missiles waiting to be fired. This Stephen Vizinczey joins the Hasidim placidly watching the smoke rising above Gaza from a nearby hilltop. The Palestinians are so evil, they want to live, they get angry, they hit back, they try to defend themselves! Condemn them! Yes, there is selective outrage here, but it isn't the critics of Israel who are guilty of it.

Labels:

gaza,

israel,

stephen vizinczey

My Brother's Keeper II

It's now a year since the beginning of Operation Cast Lead, the Israeli blitzkrieg of Gaza. Uri Avnery has a good retrospective on it at Counterpunch, showing that it was at best an ambiguous victory for Israel. The siege of Gaza goes on, however, with the US Army Corps of Engineers working with Israel to maintain it. A large protest, the Gaza Freedom March, is simmering in Cairo, to the great discomfort of the Egyptian government; the participation of Hedy Epstein, an 85-year-old Holocaust survivor from St. Louis, adds to the bad PR for both Israel and Egypt.

It's now a year since the beginning of Operation Cast Lead, the Israeli blitzkrieg of Gaza. Uri Avnery has a good retrospective on it at Counterpunch, showing that it was at best an ambiguous victory for Israel. The siege of Gaza goes on, however, with the US Army Corps of Engineers working with Israel to maintain it. A large protest, the Gaza Freedom March, is simmering in Cairo, to the great discomfort of the Egyptian government; the participation of Hedy Epstein, an 85-year-old Holocaust survivor from St. Louis, adds to the bad PR for both Israel and Egypt.But I want to write about a startling post on the Israel-Palestine conflict by Stephen Vizinczey on his blog. It's hard to believe this was actually written by Vizinczey, who wrote some insightful analysis of Soviet and American imperialism in the past. But, it seems, like many people his insight breaks down where Israel is concerned. He wrote:

The recent condemnation of Israel is a fine example of the selective outrage that ensures that there will never be peace on Earth. “We rain rockets on the Israelis, on their farms, on their nurseries, their schools. We explode bombs in their restaurants, in their supermarkets – we are going to wipe Israel off the face of the Earth! But they are so evil, they want to live, they get angry, they hit back, they try to defend themselves! Condemn them!”This makes no sense on any level. To begin at the surface, who is supposed to be speaking in his imagined quotation? Since it purports to be a "we" who "rain rockets on the Israelis," it would have to be Hamas, or since Hamas stopped firing rockets into Israel, various small independent Palestinian factions. (The bit about wiping Israel off the face of the Earth is a giveaway too.) According to Avnery, though, "The Qassams have stopped almost completely. Hamas has even imposed its authority on the small, extreme factions, which wanted to continue." Of course such groups would condemn Israel, and there's nothing "selective" about it. (Does Vizinczey expect the Palestinians to "rain rockets" on North Korea? The US?)

But Vizinczey isn't just angry at the Gazans; it seems that he's blaming everyone in the world who condemned Operation Cast Lead, none of whom rained rockets on the Israelis. Perhaps he means that Archbishop Tutu, Israeli combat veterans, Jimmy Carter (though he has recently recanted, or at least backtracked), and Roger Waters of Pink Floyd all figuratively rained rockets on Israel, or figuratively cheered on the rockets. It would have to be figuratively, or literally in the sense of figuratively, because virtually all the critics of the attack on Gaza were scrupulous in condemning rocket attacks on Israel.

As Vizinczey must know, the reason for the widespread condemnation of Operation Cast Lead, as of the 2006 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, was not that the Israelis were defending themselves, but that they were going so far beyond defense. Israeli casualties during Operation Cast Lead were one percent of Palestinian casualties; a similar disproportion has characterized most Israeli violence against the Palestinians. Indeed, many of the charges made against Hizbollah in Lebanon and against Hamas in Gaza turn out to be true of Israel instead: breaking ceasefires, for example, or using civilians as human shields.

The Stephen Vizinczey who dissected American justifications of its massive violence in Vietnam would have recognized this. The Stephen Vizinczey who jeered at white attempts to demonize slave resistance would have recognized this. The Stephen Vizinczey who fought in the 1956 Hungarian uprising against the Soviet Union would have recognized this. But today's Stephen Vizinczey joins the Israelis raining missiles on Lebanon; no doubt he would have joined the schoolgirls who signed their names on missiles waiting to be fired. This Stephen Vizinczey joins the Hasidim placidly watching the smoke rising above Gaza from a nearby hilltop. The Palestinians are so evil, they want to live, they get angry, they hit back, they try to defend themselves! Condemn them! Yes, there is selective outrage here, but it isn't the critics of Israel who are guilty of it.

The Stephen Vizinczey who dissected American justifications of its massive violence in Vietnam would have recognized this. The Stephen Vizinczey who jeered at white attempts to demonize slave resistance would have recognized this. The Stephen Vizinczey who fought in the 1956 Hungarian uprising against the Soviet Union would have recognized this. But today's Stephen Vizinczey joins the Israelis raining missiles on Lebanon; no doubt he would have joined the schoolgirls who signed their names on missiles waiting to be fired. This Stephen Vizinczey joins the Hasidim placidly watching the smoke rising above Gaza from a nearby hilltop. The Palestinians are so evil, they want to live, they get angry, they hit back, they try to defend themselves! Condemn them! Yes, there is selective outrage here, but it isn't the critics of Israel who are guilty of it.

Labels:

gaza,

israel,

stephen vizinczey

Snow Days

I'm just too lazy today to write any more, but I liked this photo I found on Blogger Play. It reminds me of winter days when I was a kid. I didn't grow up on a hog farm, but there was one down the road from us. Oddly, the blogger called this much snow a blizzard; I don't think school would have been canceled for it in northern Indiana.

I'm just too lazy today to write any more, but I liked this photo I found on Blogger Play. It reminds me of winter days when I was a kid. I didn't grow up on a hog farm, but there was one down the road from us. Oddly, the blogger called this much snow a blizzard; I don't think school would have been canceled for it in northern Indiana. While I'm doing the photo thing, here's one of mine, taken while snow was falling this past Sunday. I was able to get the falling flakes to show up. We didn't get a lot of snow, just half an inch to an inch altogether, and it's almost gone now since the sun came out today.

While I'm doing the photo thing, here's one of mine, taken while snow was falling this past Sunday. I was able to get the falling flakes to show up. We didn't get a lot of snow, just half an inch to an inch altogether, and it's almost gone now since the sun came out today.

Labels:

non-blizzard

Snow Days

I'm just too lazy today to write any more, but I liked this photo I found on Blogger Play. It reminds me of winter days when I was a kid. I didn't grow up on a hog farm, but there was one down the road from us. Oddly, the blogger called this much snow a blizzard; I don't think school would have been canceled for it in northern Indiana.

I'm just too lazy today to write any more, but I liked this photo I found on Blogger Play. It reminds me of winter days when I was a kid. I didn't grow up on a hog farm, but there was one down the road from us. Oddly, the blogger called this much snow a blizzard; I don't think school would have been canceled for it in northern Indiana. While I'm doing the photo thing, here's one of mine, taken while snow was falling this past Sunday. I was able to get the falling flakes to show up. We didn't get a lot of snow, just half an inch to an inch altogether, and it's almost gone now since the sun came out today.

While I'm doing the photo thing, here's one of mine, taken while snow was falling this past Sunday. I was able to get the falling flakes to show up. We didn't get a lot of snow, just half an inch to an inch altogether, and it's almost gone now since the sun came out today.

Labels:

non-blizzard

Fort Knox Gold plated tungsten

Gold-plated tungsten bars scandal is about to erupt

it looks that a big part of Gold bars in Banks vaults are in fact tungsten plated gold , the scandal is just starting to leak and it could cause the burst of the Gold bubble , if the general public starts losing faith in the gold not being able to spot the real from the fake cause it wouldn't be too difficult to make convincing fake gold bars out of gold-plated tungsten (which costs $30 a pound compared to $12,000 a pound for gold).

Labels:

Gold plated tungsten bars

Marvin Martian

In the past few years I've been making an effort to revisit books I read as a kid, especially by the science fiction writers who first got me interested in the genre: Robert Heinlein, Andre Norton, Ray Bradbury. Anthologies, especially Groff Conklin's, were a big help in exploring and discovering new writers, and Conklin's Invaders of Earth stood out for me, as it did for many people I think, because it included Edgar Pangborn's first science fiction story, "Angel's Egg."

"Angel's Egg" is the story of an old man who finds an egg-like object that hatches a tiny extra-terrestrial creature that looks like an angel. (When I reread the story recently for the first time in decades, I was startled to realize that the "old man" was 53. Why, he was a mere lad!) They commune telepathically, and he learns that she is from a world ten light-years away, her people have a seventy million year history, but their spaceship crashed on landing. A few survived, including her. She and her people wish to study us. She kills him, with his consent, willingly given to such a superior being. I read it much less skeptically at thirteen, of course.

I remember reading A Mirror for Observers in the early 1970s, about 20 years after it was first published, but other than that I remember nothing about it. I returned to it this month after seeing some comments about it online (via):

So I got A Mirror for Observers at the library. (It's more or less easy to find, having been reissued in 2004 by a small press that hoped to put all of Pangborn's work back into print.) It's a weird, annoying book, with all the faults of Golden Age science fiction. It has the minor disadvantage of being set in the near future -- the 1960s and 1970s -- so you can't read it now without seeing how Pangborn's future history differs from reality; but that's the fun part. My serious objections are more temperamental: a lot of sf celebrates an elect who are set apart from the herd by their high IQs and supposed rationality, and who suffer accordingly. It's a very attractive theme for adolescents, but not a fantasy that should be cultivated and encouraged; it took me a long time to shake it off. It's also the core of A Mirror for Observers.

First, there are the Martians ("Salvayans"), who fled their dying planet to settle on Terra 30,000 years ago. By a remarkable coincidence, they arrived exactly 29,000 years before the beginning of the Christian era, so you only need to subtract 29,000 from the Salvayan dates given in the story to know what year it is in the US. (30,963 becomes 1963, for example.) The Salvayans mostly observe Star Trek's Prime Directive of non-interference with the natives, though at one point we're told that "It was all right to help some of the early tribes find [?] the bow and arrow the way we did, but times have changed." Gee, thanks, Salvayans! In their benign wisdom, they began the arms race, no doubt hoping we'd kill ourselves off, but it didn't work out that way. And just as well, since the Martians have not flourished on Terra; they survived, but not much better than that. They can pass among us by the use of prosthetic makeup and a scent-killer (the narrator is glad that the automobile has made horses largely obsolete, since the equine nose could smell them out); they dabble in our arts and adopt our vices (the narrator likes cigarettes but disapproves of barbiturates as a women's weakness); but they mainly seem to be marking time until they become extinct. It's hard to create credible extraterrestrials, let alone tell a story from their point of view, and Pangborn hardly tries; well, his Martians are assimilated immigrants after thirty thousand years, hardly aliens at all by now.

The year is 30,963. Observers from the North American Missions have spotted a twelve-year-old boy, Angelo Pontevecchio, who has the potential to be, in some obscure fashion, the One. In a subterranean bunker, director Drozma disputes with the evil Namir the Abdicator.

Elmis checks into Angelo's mother's boarding house, and it's love at first sight -- not for Mom, described by the kindly Salvayans as "‘sweet-minded.’ Not much education, and on a very different psychophysical level; a fat woman in poor health" -- but for Angelo.

Art seems to be his true touchstone -- Angelo is a painter, Sharon a concert pianist -- and that's all very well, but more as an escape from humanity than a key to us. Elmis also celebrates an orbiting satellite (and remember, this novel was written before people actually put such an object in space) as the "most dramatic achievement of human science, I think, and something more than science too -- a bright finger groping at the heavens." He praises Drozma for standing "apart, watching both worlds with a clarity I have never achieved." Well, so did Namir. A Mirror for Observers is a classically individualist work, with an ethic that is barely even tribal.

"Angel's Egg" is the story of an old man who finds an egg-like object that hatches a tiny extra-terrestrial creature that looks like an angel. (When I reread the story recently for the first time in decades, I was startled to realize that the "old man" was 53. Why, he was a mere lad!) They commune telepathically, and he learns that she is from a world ten light-years away, her people have a seventy million year history, but their spaceship crashed on landing. A few survived, including her. She and her people wish to study us. She kills him, with his consent, willingly given to such a superior being. I read it much less skeptically at thirteen, of course.

"What is this 'angel' in your mind when you think of me?""Angel's Egg" announced some of Pangborn's characteristic themes and devices: sentimentality; contempt for humanity and other "lower" species, including women; an older bachelor who befriends a superior, much younger superbeing. Editor Conklin put it more nicely:

"A being men have imagined for centuries, when they thought of themselves as they might like to be and not as they are."

Many authors refuse to assume that mankind is the apex, the point of the pyramid, the tip of the top. ... Some authors take it for granted that the creatures from space will be friendly even though they are a few thousand years ahead of us ... and willing to work painstakingly with the few humans who have imagination and ability to learn, even though, in doing so, the aliens might become permanent exiles from their home planet.Pangborn had been publishing mystery/crime fiction under various pseudonyms since the 1930s, but "Angel's Egg" put him on the science fiction map. He put out several sf novels during the 1950s, along with The Trial of Callista Blake, a crime novel that had a lot in common with Grace Metalious's best-selling Peyton Place. (Sexy scandal in small New England town, world-weary older male characters brooding over small-town narrow-mindedness, beautiful and troubled young woman.) His post-nuclear holocaust novel Davy was the next work of his I read after "Angel's Egg", my fourteen-year-old's attention caught by the buff male model draped over the cover of the paperback. I followed Pangborn's work after that, but ambivalently. I appreciated his skillful, lyrical writing and its growing homoeroticism, but was never really satisfied by it either.

I remember reading A Mirror for Observers in the early 1970s, about 20 years after it was first published, but other than that I remember nothing about it. I returned to it this month after seeing some comments about it online (via):

Both biographical and textual evidence support reading [Pangborn] as gay—or rather, to fit his time period (1909-1976), homosexual, since “gay” implies a certain post-Stonewall consciousness of and confidence about sexual identity.I disagree with this critic's distinction between "gay" and "homosexual" based on "time period" -- a number of writers of Pangborn's generation, such as Christopher Isherwood (1904-1986), are properly classified as gay writers, even when (like Isherwood) they hated the word "gay." A better description of Pangborn's manner, I suggest, would be "coded" or "closeted." This is probably connected to his work being genre rather than 'literary' fiction, American rather than British or Continental, and to the wishfully pederastic model of the relationships he invents.

[Pangborn's] work supports queer readings. He writes from an outsider position assigned by heteronormative culture, and he uses that position to critique social norms and institutions. The best example is his strongest novel, A Mirror for Observers (1954). Although Patricia Bizzell, in one of the few critical pieces on this neglected writer (Dictionary of Literary Biography, volume 8), reads the novel in terms of “an intense homoerotic friendship,” that seems to me a limited or even misguided interpretation of the relationship between the book’s Martian narrator and the gifted boy, Angelo, whom he mentors. Elmis, the Martian observer, is the key to the book; ancient and benevolent, sensitive and cantankerous, he is our species’ confirmed-bachelor uncle.

So I got A Mirror for Observers at the library. (It's more or less easy to find, having been reissued in 2004 by a small press that hoped to put all of Pangborn's work back into print.) It's a weird, annoying book, with all the faults of Golden Age science fiction. It has the minor disadvantage of being set in the near future -- the 1960s and 1970s -- so you can't read it now without seeing how Pangborn's future history differs from reality; but that's the fun part. My serious objections are more temperamental: a lot of sf celebrates an elect who are set apart from the herd by their high IQs and supposed rationality, and who suffer accordingly. It's a very attractive theme for adolescents, but not a fantasy that should be cultivated and encouraged; it took me a long time to shake it off. It's also the core of A Mirror for Observers.

First, there are the Martians ("Salvayans"), who fled their dying planet to settle on Terra 30,000 years ago. By a remarkable coincidence, they arrived exactly 29,000 years before the beginning of the Christian era, so you only need to subtract 29,000 from the Salvayan dates given in the story to know what year it is in the US. (30,963 becomes 1963, for example.) The Salvayans mostly observe Star Trek's Prime Directive of non-interference with the natives, though at one point we're told that "It was all right to help some of the early tribes find [?] the bow and arrow the way we did, but times have changed." Gee, thanks, Salvayans! In their benign wisdom, they began the arms race, no doubt hoping we'd kill ourselves off, but it didn't work out that way. And just as well, since the Martians have not flourished on Terra; they survived, but not much better than that. They can pass among us by the use of prosthetic makeup and a scent-killer (the narrator is glad that the automobile has made horses largely obsolete, since the equine nose could smell them out); they dabble in our arts and adopt our vices (the narrator likes cigarettes but disapproves of barbiturates as a women's weakness); but they mainly seem to be marking time until they become extinct. It's hard to create credible extraterrestrials, let alone tell a story from their point of view, and Pangborn hardly tries; well, his Martians are assimilated immigrants after thirty thousand years, hardly aliens at all by now.

The year is 30,963. Observers from the North American Missions have spotted a twelve-year-old boy, Angelo Pontevecchio, who has the potential to be, in some obscure fashion, the One. In a subterranean bunker, director Drozma disputes with the evil Namir the Abdicator.

Namir yawned. “So? Did she mention Angelo Pontevecchio?”There are echoes here of the biblical book of Job, with Namir as Satan and Drozma as Yahweh. Namir's malignity is basically devoid of motive; he's a moustache-twirling villain from nineteenth-century melodrama. Despite his dislike for organized religion, Pangborn was a basically religious writer, with a Manichaean view of the world, and when he tried to imagine human beings "as they might like to be and not as they are," his imagination fell as short as most religious writers' have done. Drozma, "painfully old now, painfully fat with age," can do nothing but rouse the Observer Elmis from his contemplation and send him to protect Angelo. Or something.

“Of course.”

“I hope you don’t imagine you can do anything with that boy.”

“What we hear of him interests us.”

“Tchah! A human child, therefore potentially corrupt.” Namir pulled a man-made cigarette from his man-made clothes and rubbed his large human face in the smoke. “He shares that existence which another human animal has accurately described as ‘nasty, brutish, and short.’” ...

“How can you observe through a sickness of hatred?”

“I observe sharply, Drozma.”

Elmis checks into Angelo's mother's boarding house, and it's love at first sight -- not for Mom, described by the kindly Salvayans as "‘sweet-minded.’ Not much education, and on a very different psychophysical level; a fat woman in poor health" -- but for Angelo.

I knew him at once, this golden-skinned boy with eyes so profoundly dark that iris and pupil blended in one sparkle. … When we admit that the simplest mind is a continuing mystery, what height of arrogance it would be to say that I know Angelo!Angelo is precocious, reads Plato and Hegel, shows his sensual paintings to old ladies:

Three mares in a high meadow, heads lifted to the approach of a vast red stallion. Colors roared like mountain wind. A meeting of wind and sunlight, savage and joyful, shoutingly and gorgeously sexual. Angelo should have been spanked.(Yeah, you'd enjoy that, wouldn't you?) Namir lurks in the background, trying to turn Angelo away from his path, whatever it is. Oh, and there's ten-year-old Sharon Brand, whose father runs the local delicatessen. She's a squirm-inducing Shirley Temple retread -- movies seem to have been the extent of Pangborn's interaction with children, boys or girls.

"Look," she said. "Heck, could this autothentically happen, I mean for true?" ...Namir succeeds in diverting Angelo from his path, whatever it is, but only for a season. In Part Two, set in 30,972, everyone changes names, and Pangborn tries to depict a nativist, cult-like political movement with a mad scientist, followed by cataclysm that wipes out about a third of the human race. Angelo, wounded spiritually, has withdrawn into himself. Elmis comes to the rescue, but with only partial success. The important thing is that Angelo and Sharon are reunited, and Angelo resumes painting. Elmis rhapsodizes:

"Mr. Miles, how can I ever abdiquately thank you?" ...

"By the way, I love you beyond comprehemption."

Never, beautiful earth, never even at the height of the human storms have I forgotten you, my planet Earth, your forests and your fields, your oceans, the serenity of your mountains; he meadows, the continuing rivers, the incorruptible promise of returning spring.Or, as Bette Davis told Paul Henreid at the end of Now, Voyager, "Don't ask for the moon when we have ... the stars!" I just remembered something someone wrote about Carlos Castaneda and his fictional Yaqui men of knowledge and power: that they love the Earth, but not the people on it. That seems to fit Pangborn as well. There are frequent references in A Mirror for Observers to the need for an advance to an "empirical ethics," but no hint of what Angelo is supposed to contribute to it, or what difference it would make. Pangborn kills off a major chunk of humanity including the faceless masses of Asia and Africa, with hardly a tremor; after all, we just clutter up those forests, fields, oceans and rivers, and corrupt the promise of spring.

Art seems to be his true touchstone -- Angelo is a painter, Sharon a concert pianist -- and that's all very well, but more as an escape from humanity than a key to us. Elmis also celebrates an orbiting satellite (and remember, this novel was written before people actually put such an object in space) as the "most dramatic achievement of human science, I think, and something more than science too -- a bright finger groping at the heavens." He praises Drozma for standing "apart, watching both worlds with a clarity I have never achieved." Well, so did Namir. A Mirror for Observers is a classically individualist work, with an ethic that is barely even tribal.

Labels:

edgar pangborn,

mirror for observers

Marvin Martian

In the past few years I've been making an effort to revisit books I read as a kid, especially by the science fiction writers who first got me interested in the genre: Robert Heinlein, Andre Norton, Ray Bradbury. Anthologies, especially Groff Conklin's, were a big help in exploring and discovering new writers, and Conklin's Invaders of Earth stood out for me, as it did for many people I think, because it included Edgar Pangborn's first science fiction story, "Angel's Egg."

"Angel's Egg" is the story of an old man who finds an egg-like object that hatches a tiny extra-terrestrial creature that looks like an angel. (When I reread the story recently for the first time in decades, I was startled to realize that the "old man" was 53. Why, he was a mere lad!) They commune telepathically, and he learns that she is from a world ten light-years away, her people have a seventy million year history, but their spaceship crashed on landing. A few survived, including her. She and her people wish to study us. She kills him, with his consent, willingly given to such a superior being. I read it much less skeptically at thirteen, of course.

I remember reading A Mirror for Observers in the early 1970s, about 20 years after it was first published, but other than that I remember nothing about it. I returned to it this month after seeing some comments about it online (via):

So I got A Mirror for Observers at the library. (It's more or less easy to find, having been reissued in 2004 by a small press that hoped to put all of Pangborn's work back into print.) It's a weird, annoying book, with all the faults of Golden Age science fiction. It has the minor disadvantage of being set in the near future -- the 1960s and 1970s -- so you can't read it now without seeing how Pangborn's future history differs from reality; but that's the fun part. My serious objections are more temperamental: a lot of sf celebrates an elect who are set apart from the herd by their high IQs and supposed rationality, and who suffer accordingly. It's a very attractive theme for adolescents, but not a fantasy that should be cultivated and encouraged; it took me a long time to shake it off. It's also the core of A Mirror for Observers.

First, there are the Martians ("Salvayans"), who fled their dying planet to settle on Terra 30,000 years ago. By a remarkable coincidence, they arrived exactly 29,000 years before the beginning of the Christian era, so you only need to subtract 29,000 from the Salvayan dates given in the story to know what year it is in the US. (30,963 becomes 1963, for example.) The Salvayans mostly observe Star Trek's Prime Directive of non-interference with the natives, though at one point we're told that "It was all right to help some of the early tribes find [?] the bow and arrow the way we did, but times have changed." Gee, thanks, Salvayans! In their benign wisdom, they began the arms race, no doubt hoping we'd kill ourselves off, but it didn't work out that way. And just as well, since the Martians have not flourished on Terra; they survived, but not much better than that. They can pass among us by the use of prosthetic makeup and a scent-killer (the narrator is glad that the automobile has made horses largely obsolete, since the equine nose could smell them out); they dabble in our arts and adopt our vices (the narrator likes cigarettes but disapproves of barbiturates as a women's weakness); but they mainly seem to be marking time until they become extinct. It's hard to create credible extraterrestrials, let alone tell a story from their point of view, and Pangborn hardly tries; well, his Martians are assimilated immigrants after thirty thousand years, hardly aliens at all by now.

The year is 30,963. Observers from the North American Missions have spotted a twelve-year-old boy, Angelo Pontevecchio, who has the potential to be, in some obscure fashion, the One. In a subterranean bunker, director Drozma disputes with the evil Namir the Abdicator.

Elmis checks into Angelo's mother's boarding house, and it's love at first sight -- not for Mom, described by the kindly Salvayans as "‘sweet-minded.’ Not much education, and on a very different psychophysical level; a fat woman in poor health" -- but for Angelo.

Art seems to be his true touchstone -- Angelo is a painter, Sharon a concert pianist -- and that's all very well, but more as an escape from humanity than a key to us. Elmis also celebrates an orbiting satellite (and remember, this novel was written before people actually put such an object in space) as the "most dramatic achievement of human science, I think, and something more than science too -- a bright finger groping at the heavens." He praises Drozma for standing "apart, watching both worlds with a clarity I have never achieved." Well, so did Namir. A Mirror for Observers is a classically individualist work, with an ethic that is barely even tribal.

"Angel's Egg" is the story of an old man who finds an egg-like object that hatches a tiny extra-terrestrial creature that looks like an angel. (When I reread the story recently for the first time in decades, I was startled to realize that the "old man" was 53. Why, he was a mere lad!) They commune telepathically, and he learns that she is from a world ten light-years away, her people have a seventy million year history, but their spaceship crashed on landing. A few survived, including her. She and her people wish to study us. She kills him, with his consent, willingly given to such a superior being. I read it much less skeptically at thirteen, of course.

"What is this 'angel' in your mind when you think of me?""Angel's Egg" announced some of Pangborn's characteristic themes and devices: sentimentality; contempt for humanity and other "lower" species, including women; an older bachelor who befriends a superior, much younger superbeing. Editor Conklin put it more nicely:

"A being men have imagined for centuries, when they thought of themselves as they might like to be and not as they are."

Many authors refuse to assume that mankind is the apex, the point of the pyramid, the tip of the top. ... Some authors take it for granted that the creatures from space will be friendly even though they are a few thousand years ahead of us ... and willing to work painstakingly with the few humans who have imagination and ability to learn, even though, in doing so, the aliens might become permanent exiles from their home planet.Pangborn had been publishing mystery/crime fiction under various pseudonyms since the 1930s, but "Angel's Egg" put him on the science fiction map. He put out several sf novels during the 1950s, along with The Trial of Callista Blake, a crime novel that had a lot in common with Grace Metalious's best-selling Peyton Place. (Sexy scandal in small New England town, world-weary older male characters brooding over small-town narrow-mindedness, beautiful and troubled young woman.) His post-nuclear holocaust novel Davy was the next work of his I read after "Angel's Egg", my fourteen-year-old's attention caught by the buff male model draped over the cover of the paperback. I followed Pangborn's work after that, but ambivalently. I appreciated his skillful, lyrical writing and its growing homoeroticism, but was never really satisfied by it either.

I remember reading A Mirror for Observers in the early 1970s, about 20 years after it was first published, but other than that I remember nothing about it. I returned to it this month after seeing some comments about it online (via):

Both biographical and textual evidence support reading [Pangborn] as gay—or rather, to fit his time period (1909-1976), homosexual, since “gay” implies a certain post-Stonewall consciousness of and confidence about sexual identity.I disagree with this critic's distinction between "gay" and "homosexual" based on "time period" -- a number of writers of Pangborn's generation, such as Christopher Isherwood (1904-1986), are properly classified as gay writers, even when (like Isherwood) they hated the word "gay." A better description of Pangborn's manner, I suggest, would be "coded" or "closeted." This is probably connected to his work being genre rather than 'literary' fiction, American rather than British or Continental, and to the wishfully pederastic model of the relationships he invents.

[Pangborn's] work supports queer readings. He writes from an outsider position assigned by heteronormative culture, and he uses that position to critique social norms and institutions. The best example is his strongest novel, A Mirror for Observers (1954). Although Patricia Bizzell, in one of the few critical pieces on this neglected writer (Dictionary of Literary Biography, volume 8), reads the novel in terms of “an intense homoerotic friendship,” that seems to me a limited or even misguided interpretation of the relationship between the book’s Martian narrator and the gifted boy, Angelo, whom he mentors. Elmis, the Martian observer, is the key to the book; ancient and benevolent, sensitive and cantankerous, he is our species’ confirmed-bachelor uncle.

So I got A Mirror for Observers at the library. (It's more or less easy to find, having been reissued in 2004 by a small press that hoped to put all of Pangborn's work back into print.) It's a weird, annoying book, with all the faults of Golden Age science fiction. It has the minor disadvantage of being set in the near future -- the 1960s and 1970s -- so you can't read it now without seeing how Pangborn's future history differs from reality; but that's the fun part. My serious objections are more temperamental: a lot of sf celebrates an elect who are set apart from the herd by their high IQs and supposed rationality, and who suffer accordingly. It's a very attractive theme for adolescents, but not a fantasy that should be cultivated and encouraged; it took me a long time to shake it off. It's also the core of A Mirror for Observers.

First, there are the Martians ("Salvayans"), who fled their dying planet to settle on Terra 30,000 years ago. By a remarkable coincidence, they arrived exactly 29,000 years before the beginning of the Christian era, so you only need to subtract 29,000 from the Salvayan dates given in the story to know what year it is in the US. (30,963 becomes 1963, for example.) The Salvayans mostly observe Star Trek's Prime Directive of non-interference with the natives, though at one point we're told that "It was all right to help some of the early tribes find [?] the bow and arrow the way we did, but times have changed." Gee, thanks, Salvayans! In their benign wisdom, they began the arms race, no doubt hoping we'd kill ourselves off, but it didn't work out that way. And just as well, since the Martians have not flourished on Terra; they survived, but not much better than that. They can pass among us by the use of prosthetic makeup and a scent-killer (the narrator is glad that the automobile has made horses largely obsolete, since the equine nose could smell them out); they dabble in our arts and adopt our vices (the narrator likes cigarettes but disapproves of barbiturates as a women's weakness); but they mainly seem to be marking time until they become extinct. It's hard to create credible extraterrestrials, let alone tell a story from their point of view, and Pangborn hardly tries; well, his Martians are assimilated immigrants after thirty thousand years, hardly aliens at all by now.

The year is 30,963. Observers from the North American Missions have spotted a twelve-year-old boy, Angelo Pontevecchio, who has the potential to be, in some obscure fashion, the One. In a subterranean bunker, director Drozma disputes with the evil Namir the Abdicator.

Namir yawned. “So? Did she mention Angelo Pontevecchio?”There are echoes here of the biblical book of Job, with Namir as Satan and Drozma as Yahweh. Namir's malignity is basically devoid of motive; he's a moustache-twirling villain from nineteenth-century melodrama. Despite his dislike for organized religion, Pangborn was a basically religious writer, with a Manichaean view of the world, and when he tried to imagine human beings "as they might like to be and not as they are," his imagination fell as short as most religious writers' have done. Drozma, "painfully old now, painfully fat with age," can do nothing but rouse the Observer Elmis from his contemplation and send him to protect Angelo. Or something.

“Of course.”

“I hope you don’t imagine you can do anything with that boy.”

“What we hear of him interests us.”

“Tchah! A human child, therefore potentially corrupt.” Namir pulled a man-made cigarette from his man-made clothes and rubbed his large human face in the smoke. “He shares that existence which another human animal has accurately described as ‘nasty, brutish, and short.’” ...

“How can you observe through a sickness of hatred?”

“I observe sharply, Drozma.”

Elmis checks into Angelo's mother's boarding house, and it's love at first sight -- not for Mom, described by the kindly Salvayans as "‘sweet-minded.’ Not much education, and on a very different psychophysical level; a fat woman in poor health" -- but for Angelo.

I knew him at once, this golden-skinned boy with eyes so profoundly dark that iris and pupil blended in one sparkle. … When we admit that the simplest mind is a continuing mystery, what height of arrogance it would be to say that I know Angelo!Angelo is precocious, reads Plato and Hegel, shows his sensual paintings to old ladies:

Three mares in a high meadow, heads lifted to the approach of a vast red stallion. Colors roared like mountain wind. A meeting of wind and sunlight, savage and joyful, shoutingly and gorgeously sexual. Angelo should have been spanked.(Yeah, you'd enjoy that, wouldn't you?) Namir lurks in the background, trying to turn Angelo away from his path, whatever it is. Oh, and there's ten-year-old Sharon Brand, whose father runs the local delicatessen. She's a squirm-inducing Shirley Temple retread -- movies seem to have been the extent of Pangborn's interaction with children, boys or girls.

"Look," she said. "Heck, could this autothentically happen, I mean for true?" ...Namir succeeds in diverting Angelo from his path, whatever it is, but only for a season. In Part Two, set in 30,972, everyone changes names, and Pangborn tries to depict a nativist, cult-like political movement with a mad scientist, followed by cataclysm that wipes out about a third of the human race. Angelo, wounded spiritually, has withdrawn into himself. Elmis comes to the rescue, but with only partial success. The important thing is that Angelo and Sharon are reunited, and Angelo resumes painting. Elmis rhapsodizes:

"Mr. Miles, how can I ever abdiquately thank you?" ...

"By the way, I love you beyond comprehemption."

Never, beautiful earth, never even at the height of the human storms have I forgotten you, my planet Earth, your forests and your fields, your oceans, the serenity of your mountains; he meadows, the continuing rivers, the incorruptible promise of returning spring.Or, as Bette Davis told Paul Henreid at the end of Now, Voyager, "Don't ask for the moon when we have ... the stars!" I just remembered something someone wrote about Carlos Castaneda and his fictional Yaqui men of knowledge and power: that they love the Earth, but not the people on it. That seems to fit Pangborn as well. There are frequent references in A Mirror for Observers to the need for an advance to an "empirical ethics," but no hint of what Angelo is supposed to contribute to it, or what difference it would make. Pangborn kills off a major chunk of humanity including the faceless masses of Asia and Africa, with hardly a tremor; after all, we just clutter up those forests, fields, oceans and rivers, and corrupt the promise of spring.

Art seems to be his true touchstone -- Angelo is a painter, Sharon a concert pianist -- and that's all very well, but more as an escape from humanity than a key to us. Elmis also celebrates an orbiting satellite (and remember, this novel was written before people actually put such an object in space) as the "most dramatic achievement of human science, I think, and something more than science too -- a bright finger groping at the heavens." He praises Drozma for standing "apart, watching both worlds with a clarity I have never achieved." Well, so did Namir. A Mirror for Observers is a classically individualist work, with an ethic that is barely even tribal.

Labels:

edgar pangborn,

mirror for observers

Law professors' conference addresses needs of same-sex partners in a "defense of marriage" state

Next week, the Association of American Law Schools will hold its annual meeting in New Orleans. This is the annual meeting of law professors from across the country. In acknowledgement of the needs of same-sex and unmarried partners in a state with a "defense of marriage" act, the AALS's executive director, Susan Westerberg Prager, today sent out the following message to all attendees. I am reprinting it in full here because I hope other associations with plans to hold meetings in states that refuse to recognize the needs of same-sex and unmarried different-sex partners will follow this fine example provided by the AALS.

December 28, 2009

Message to Annual Meeting Attendees:

Because Louisiana has placed in its constitution what is commonly referred to as a "Defense of Marriage" law, we have put in place some precautionary assistance for Annual Meeting registrants and their guests. This message is intended for those of you who are either unmarried but have a partner, married but in a marriage that would not be recognized by Louisiana Law, or who have a family member in one of these categories who will travel with you to New Orleans. Even in states that do not have such a law, there have been reports of hospital personnel who will not allow same sex partners visitation accorded family members, or who may even attempt to make the exercise of a health care power of attorney difficult. (For convenience of communication, I use the term "partner" in this message to refer to married and unmarried partners.)

AALS Managing Director Jane La Barbera has explored the practices in New Orleans, and has vigorously emphasized to the New Orleans Convention Bureau our concerns. We have received strong assurances that health care Powers of Attorney will be recognized by hospitals in the region, regardless of the relationship of the patient and the person holding the power. We have had that verified by the leadership of the Tulane Medical Center.

However, we do want to be of assistance to you in New Orleans if any of the following difficulties occur during the AALS Annual Meeting. Should any attendee or guest of an attendee experience a hospital refusing access (to the patient) to the patient's partner, or refusing the partner access to the patient's hospital doctors, or if hospital personnel are reluctant to recognize a power of attorney, we are providing the following list of individuals who are available to assist you. (The first is a local lawyer provided to AALS by the New Orleans Convention and Visitors Bureau without fee to AALS or our registrants. The second and third are AALS volunteers: Taylor is a Professor colleague who is incoming chair of the AALS Section on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Issues, and Jim is the lawyer spouse of the longtime Professor and Dean who is writing this message.) (I am omitting the phone numbers provided for the lawyers --np)

1. Robert M. Walmsley, Jr., Fishman, Haygood, Phelps, Walmsley, Willis & Swanson L.L.P

2. Professor Taylor Flynn

3. Jim Prager

All of these individuals stand ready to assist you with the hospital staff, and you should not hesitate to call upon them. They will assist in communicating with the hospital staff, working their way through the hospital's chain of authority if necessary. We recommend that you try to reach Mr. Walmsley first unless the hour of your call would make it unlikely that he would be at his firm.

Should you have difficulty reaching a member of this group, contact the AALS Office at the Hilton New Orleans Riverside by calling the hotel at (304) 561-0500 and asking for the AALS Office in the Marlborough Room. If the office is closed, make sure you have left messages for both Taylor and Jim, and try each of them again. I do recommend that you and your partner each carry with you a health care power of attorney. Even in extreme circumstances where the power contemplates are not present, it is a useful statement of your point of view about the person(s) closest to you, and that can help get the designated individual access to you and to your hospital doctor if you are hospitalized.

We, of course, hope that no attendee or family member is faced with the need to navigate such a problem, but we do want you to call upon us should you find yourself in circumstances where we can be of help. We very much look forward to welcoming all attendees and their guests to the 2010 AALS Annual Meeting.

December 28, 2009

Message to Annual Meeting Attendees:

Because Louisiana has placed in its constitution what is commonly referred to as a "Defense of Marriage" law, we have put in place some precautionary assistance for Annual Meeting registrants and their guests. This message is intended for those of you who are either unmarried but have a partner, married but in a marriage that would not be recognized by Louisiana Law, or who have a family member in one of these categories who will travel with you to New Orleans. Even in states that do not have such a law, there have been reports of hospital personnel who will not allow same sex partners visitation accorded family members, or who may even attempt to make the exercise of a health care power of attorney difficult. (For convenience of communication, I use the term "partner" in this message to refer to married and unmarried partners.)

AALS Managing Director Jane La Barbera has explored the practices in New Orleans, and has vigorously emphasized to the New Orleans Convention Bureau our concerns. We have received strong assurances that health care Powers of Attorney will be recognized by hospitals in the region, regardless of the relationship of the patient and the person holding the power. We have had that verified by the leadership of the Tulane Medical Center.

However, we do want to be of assistance to you in New Orleans if any of the following difficulties occur during the AALS Annual Meeting. Should any attendee or guest of an attendee experience a hospital refusing access (to the patient) to the patient's partner, or refusing the partner access to the patient's hospital doctors, or if hospital personnel are reluctant to recognize a power of attorney, we are providing the following list of individuals who are available to assist you. (The first is a local lawyer provided to AALS by the New Orleans Convention and Visitors Bureau without fee to AALS or our registrants. The second and third are AALS volunteers: Taylor is a Professor colleague who is incoming chair of the AALS Section on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Issues, and Jim is the lawyer spouse of the longtime Professor and Dean who is writing this message.) (I am omitting the phone numbers provided for the lawyers --np)

1. Robert M. Walmsley, Jr., Fishman, Haygood, Phelps, Walmsley, Willis & Swanson L.L.P

2. Professor Taylor Flynn

3. Jim Prager

All of these individuals stand ready to assist you with the hospital staff, and you should not hesitate to call upon them. They will assist in communicating with the hospital staff, working their way through the hospital's chain of authority if necessary. We recommend that you try to reach Mr. Walmsley first unless the hour of your call would make it unlikely that he would be at his firm.

Should you have difficulty reaching a member of this group, contact the AALS Office at the Hilton New Orleans Riverside by calling the hotel at (304) 561-0500 and asking for the AALS Office in the Marlborough Room. If the office is closed, make sure you have left messages for both Taylor and Jim, and try each of them again. I do recommend that you and your partner each carry with you a health care power of attorney. Even in extreme circumstances where the power contemplates are not present, it is a useful statement of your point of view about the person(s) closest to you, and that can help get the designated individual access to you and to your hospital doctor if you are hospitalized.

We, of course, hope that no attendee or family member is faced with the need to navigate such a problem, but we do want you to call upon us should you find yourself in circumstances where we can be of help. We very much look forward to welcoming all attendees and their guests to the 2010 AALS Annual Meeting.

Labels:

AALS,

advance health care directives,

DOMA

Contemplating gay and lesbian families in New Mexico in 2010

I'll be heading home to DC tomorrow from our annual end-of-year sojourn to our second home in Las Cruces, NM. There's lots to keep an eye on in New Mexico in the coming weeks.

On January 1, 2010, New Mexico's new parentage laws go into effect. Read Sections 7-703 & 704 of the new statute. It says that "a person who...consents to assisted reproduction...with the intent to be the parent of a child is a parent of the resulting child." The consent is supposed to be in writing before the assisted reproduction takes place. If the requisite written consent does not take place, the intended parent is still a parent "if the parent, during the first two years of the child's life, resided in the same household with the child and openly held out the child as the parent’s own."

New Mexico thus becomes the second jurisdiction in the country to recognize the parentage of the same-sex partner of a woman who conceives through donor insemination. The District of Columbia was the first. Because the DC statute also amended the law governing birth certificates, lesbian couples in DC can now receive a birth certificate naming both women as parents. It remains to be seen whether New Mexico will make it easy for lesbian couples to obtain original birth certificates listing both moms. Otherwise, the couple will need to seek a parentage order from a court. Even if the birth certificate does list both moms, the couple should get a court order of parentage or adoption to guarantee that other states will recognize both women as parents. As I've said about lesbian moms in DC, only a court order is entitled to "full faith and credit" in other states.

As for couple recognition, New Mexico is one of a small handful of states that has no "defense of marriage act." But it also has no legal status available to same-sex couples. There will be numerous opportunities for the state and the courts to determine whether same-sex couples married elsewhere will be recognized as married in New Mexico. Albuquerque attorney N. Lynn Perls reported earlier this year that when a child is born to a lesbian couple married elsewhere the state will issue a birth certificate naming both women as parents if there is also evidence of no other parent (meaning, I assume, proof of anonymous donor insemination or perhaps known donor insemination in a state that makes clear the donor is not a parent).

Governor Bill Richardson supports domestic partnership legislation, but the bill introduced in the 2009 legislative session failed. Rumor has it he will try again. This year's session is only 30 days (January 19 to February 18) so the suspense won't last long. To date, no DP bill has been pre-filed. (A DOMA bill has been pre-filed, calling for a vote on a constitutional amendment stating that marriage is only between a man and a woman; no one thinks there's danger of that bill passing.) Equality New Mexico will be front and center on these legislative issues.

Meanwhile, when discussing New Mexico I always like to mention that unmarried partners are entitled to make medical decisions for each other here, even without medical powers of attorney. If a person isn't married, top priority in the absence of a medical power of attorney goes to "an individual in a long-term relationship of indefinite duration with the patient in which the individual has demonstrated an actual commitment to the patient similar to the commitment of a spouse and in which the individual and the patient consider themselves to be responsible for each other's well-being." (That's N.M. Stat 24-7A-5). New Mexico also allows an unmarried partner to recover damages under certain circumstances if his or her partner dies as the result of someone's negligence. This makes New Mexico one of the states that sometimes values all families, along the lines I advocate in my book.

On January 1, 2010, New Mexico's new parentage laws go into effect. Read Sections 7-703 & 704 of the new statute. It says that "a person who...consents to assisted reproduction...with the intent to be the parent of a child is a parent of the resulting child." The consent is supposed to be in writing before the assisted reproduction takes place. If the requisite written consent does not take place, the intended parent is still a parent "if the parent, during the first two years of the child's life, resided in the same household with the child and openly held out the child as the parent’s own."

New Mexico thus becomes the second jurisdiction in the country to recognize the parentage of the same-sex partner of a woman who conceives through donor insemination. The District of Columbia was the first. Because the DC statute also amended the law governing birth certificates, lesbian couples in DC can now receive a birth certificate naming both women as parents. It remains to be seen whether New Mexico will make it easy for lesbian couples to obtain original birth certificates listing both moms. Otherwise, the couple will need to seek a parentage order from a court. Even if the birth certificate does list both moms, the couple should get a court order of parentage or adoption to guarantee that other states will recognize both women as parents. As I've said about lesbian moms in DC, only a court order is entitled to "full faith and credit" in other states.

As for couple recognition, New Mexico is one of a small handful of states that has no "defense of marriage act." But it also has no legal status available to same-sex couples. There will be numerous opportunities for the state and the courts to determine whether same-sex couples married elsewhere will be recognized as married in New Mexico. Albuquerque attorney N. Lynn Perls reported earlier this year that when a child is born to a lesbian couple married elsewhere the state will issue a birth certificate naming both women as parents if there is also evidence of no other parent (meaning, I assume, proof of anonymous donor insemination or perhaps known donor insemination in a state that makes clear the donor is not a parent).

Governor Bill Richardson supports domestic partnership legislation, but the bill introduced in the 2009 legislative session failed. Rumor has it he will try again. This year's session is only 30 days (January 19 to February 18) so the suspense won't last long. To date, no DP bill has been pre-filed. (A DOMA bill has been pre-filed, calling for a vote on a constitutional amendment stating that marriage is only between a man and a woman; no one thinks there's danger of that bill passing.) Equality New Mexico will be front and center on these legislative issues.

Meanwhile, when discussing New Mexico I always like to mention that unmarried partners are entitled to make medical decisions for each other here, even without medical powers of attorney. If a person isn't married, top priority in the absence of a medical power of attorney goes to "an individual in a long-term relationship of indefinite duration with the patient in which the individual has demonstrated an actual commitment to the patient similar to the commitment of a spouse and in which the individual and the patient consider themselves to be responsible for each other's well-being." (That's N.M. Stat 24-7A-5). New Mexico also allows an unmarried partner to recover damages under certain circumstances if his or her partner dies as the result of someone's negligence. This makes New Mexico one of the states that sometimes values all families, along the lines I advocate in my book.

Giving Head, and Taking It Away

A few posts back I threw a small conniption over the corporate / body metaphor of nations, inspired by poet Joy Harjo's line that "a nation is a person with a soul." I mentioned that this is a fascist doctrine, spluttering out some of what bothered me about it, but didn't get the important parts, so here's another try.

As I wrote before, in the Body Politic individuals may become mere cells to brushed off like dandruff when they're no longer needed. But some cells are more valued than others. The body is made up, in Paul the Apostle's imagery, of various members (Romans 12:3-8):

I'm digressing a bit here, but these passages have been both influential and representative -- by which I mean that Paul didn't make up these metaphors. He was borrowing a metaphor that his congregations would recognize and understand from other areas of their world, and applied it to his churches. And the metaphor persists today, even when it's not explicitly applied. Those who remember the US invasion of Iraq, our Operation Infinite Justice (I know, it's like so 2003! I should look to the future, not the past) will recall that politicians and pundits alike spoke of striking at Saddam Hussein, though in fact we hardly touched him for quite a while. The same language had been used in the first Gulf War in 1991, and during the Clinton administration too. This equation of Iraq's "head," Saddam, with the country made it easy for Americans to ignore the thousands of innocent people we were killing and hurting. They simply didn't figure in the festival of lights that was Shock and Awe.

I was surprised when Saddam was actually captured and executed -- in general heads of state prefer not to go after other heads of state. It's like a scene that was often used in old cartoons: two big guys square off for a fight, one says, "Take that!" and hits a small nerdy guy standing nearby. The other big guy bristles, growls, "Oh, yeah? Well, take that!" and hits the nerdy guy again. And so on: they never lay a finger on each other. And it may not be coincidental that the last American President to lay hands on another head of state was Bush's father, in his attack on Panama in 1989. (And as in the case of Saddam Hussein, Manuel Noriega had been a protected American client until he stopped being useful to us.) Ronald Reagan's 1986 blitzkrieg of Libya, though ostensibly directed at its leader Qadafy, killed civilians, including Qadafy's adopted 15-month-old daughter. Take that, Qadafy! (Americans do not react kindly when the same tactic is applied to us.)